Will This Trend Continue and How Will Cities Adapt and Regenerate in the Aftermath?

Many of the world’s largest cities suffer from the same complaint — their housing market is out of reach for most of their residents. While Hong Kong vies for the honor of the world’s most expensive city, many cities in North America have similar issues with a lack of affordable housing. San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, plus Vancouver and Toronto in Canada, all have hyper-inflated house prices, and rents that leave residents that either choose or need to live there, often spending more than half of their income on housing while many low- to middle-income families have about as much chance of flying to the moon as they have of ever getting a foot on the housing ladder.

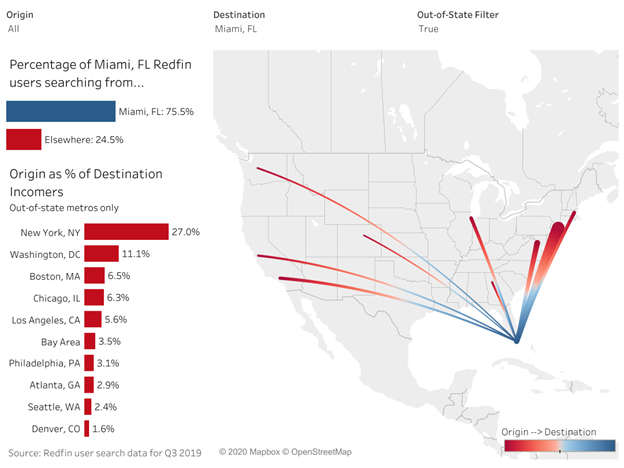

For a city like New York, the escalating cost of rent has been driving residents to move out of the city for some years now; becoming a coronavirus hotspot may have just proved the tipping point that has persuaded even more residents to join the exodus. Seeing, with horror, one’s city become one of the hardest hit areas in the US, must give people pause, and make them dream of living in a less densely populated area. For several years now, New York City has been a net exporter with more than 180,000 more people moving out of the city than moving in during 2018[1]. Roughly 5% of New York’s population have already left, while as many as 40% are seriously considering a move[2]. According to Carl Campanile in a report for the New York Post last December, two major destinations for these escapees have been New Jersey (16% and Florida (21.3%). Reasons for the attractions of these two states will likely depend on the age and life stage of those moving. New Jersey is still cheaper than New York for housing but close enough to be commutable. Florida’s appeal may be as much to do with seeking sunshine and an escape from frigid New York winters, and may appeal more to older residents. Whatever the reason, the disastrous effects of COVID-19 in New York are causing many to wonder if living in a densely populated city is really in their best interests.

In the case of New York, it may not be simply a matter of how many people there are per square mile, in fact some of the more densely populated areas have fared better than those more sparsely populated,[3] but more the economic and racial divides that epitomize some of the poorest areas.

“It’s not that there are too many people in cities,” says Dr. Mary T. Bassett, writing in The Times. “It’s that too many of their residents are poor, and many of them are members of the especially vulnerable black, Latino and Asian populations.”

It is certainly no coincidence that residents in poorer neighborhoods may already be living below the poverty line, do not have the luxury of working from home, and in fact need to work to survive, even when that means traveling on crowded subway trains and/or working in crowded conditions where social distancing is impossible.

What does this all mean for the future of cities like New York? What will such cities look like when the virus has eventually receded, or a vaccine has been found? Will we — by then — be so conditioned to social distancing that we simply continue? Will we ever happily return to crowded commuter subway trains?

Residents of most North American cities will have seen widespread, permanent closures among their favorite restaurants and stores as a result of COVID-19, and we anticipate that cities may look quite different a year or so from now. With restaurants, theaters, museums, stores, and cafes all closed — at least temporarily — and access to parks and green areas still limited, many of the apparent advantages of urban living have suddenly ceased to exist, making the high cost of living in urban centers appear far less justifiable — for now.

Nonetheless, many younger adults still prefer urban neighborhoods and may be less likely to be wooed by the suburbs or small towns than were their parents’ generation[4]. Since, despite the pandemic, rents are not only holding their own but still actually rising, it would seem that major North American cities will survive and recover. However, if municipalities learn nothing else from this crisis, they should surely envisage a very different kind of city.

To attract people to urban life, the question of affordable housing must be addressed; there is a need for denser housing that caters for mixed incomes and ethnicities that presents an opportunity for real estate investments. A range of affordable housing — for varied income levels — within an easy commuting distance of one’s employment, and provision for communal green space would be the ideal. The continued trend of developing ‘livable’ cities where one can live, work and play in the same neighborhood would also help to encourage residents to stay in the city. This trend will be particularly driven by decreased commuting as a result of COVID-19, with the added advantage of cutting down on emissions and thus helping both public health and the climate crises.

Working remotely has been one of the greater trends to arise as a result of lockdowns and many of those who have discovered the freedom of not spending hours sitting in traffic, or in crowded trains daily, will likely want this trend to continue — at least part of the time. It is attractive to employers also, who have discovered that meetings on Zoom can be just as productive and that employees working from their home offices potentially save them thousands of dollars on office space and its associated costs. Forward-thinking city planners are already adapting roads — previously dominated by automobiles — to accommodate more bike lanes and additional space for pedestrians. We see evidence of this in cities around the globe.

“Barcelona has built 21 km of new bike lanes, Berlin has widened bike lanes for safer passing and New York City mayor Bill de Blasio has committed to 100 miles of open streets,” says Lily Hansen-Gillis, writing for Canadian Cycling. “Paris has created an incredible 650 km of ‘pop-up cycleways’ across the entire city for commuters.”[5]

Copenhagen and Amsterdam may lead the world in terms of being bike-friendly cities — 35% of people commute by bike in Copenhagen — but US cities such as Portland, Oregon, and Boulder, Colorado, are not far behind.

We can also envisage pressure on public transit increasing, if suburbanites can no longer readily drive into a city because of decreased traffic lanes. But transit cannot continue as it is at present; flexible working hours to avoid overcrowding at rush hours are just one possible solution; though more spacious and comfortable trains may be demanded also.

Let us hope that the silver lining to this pandemic is that, as we emerge from this disaster, we see real change in our major cities.

[1] Carl Campanile — New York Post — https://nypost.com/2019/12/31/new-york-residents-fleeing-to-sunny-florida-and-new-jersey-study/ December 2019

[2] Spencer Bokat-Lindell — New York Times — https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/opinion/cities-coronavirus.html May 2020

[3] Spencer Bokat-Lindell — New York Times — https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/opinion/cities-coronavirus.html May 2020

[4] Joe Cortright — New York Times — https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/opinion/cities-coronavirus.html May 2020

[5] Lily Hansen-Gillis — Canadian Cycling Magazine — https://cyclingmagazine.ca/sections/news/while-many-canadian-cities-implement-emergency-bike-lanes-some-lag-behind-in-their-response/ April 2020